May 2003 | ||||

| ||||

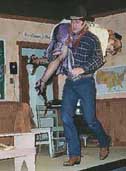

It is early March, so the drive takes me past snow-dusted fields. Hoover Dam Reservoir is frozen, and the bridge that spans its width is slick with that evening's icy rain. The houses I pass look snug and fit. Many have been standing up to winter's elements for a century or more. Tonight's entertainment is the opening night performance of William Inge's play, Bus Stop. The play tells the story of a group of travelers — a couple of cowboys, a lounge singer, a professor — taking shelter in a diner for the duration of a snowstorm in 1955 By 8 p.m., the audience of 88 people are settled into their seats. Seventy-eight are packed into the six rows of theater seats and an extra 10 people are on folding chairs in the two aisles. The house lights dim, and Jennifer Radomski, 15, as the waitress Elma Duckworth, and Tori Pollitt, 31, as the owner of Grace's Diner, slip onto the stage in the dark. When Pollitt jiggles the receiver of a phone on the set, making a clicking sound, the stage lights gradually brighten until the stage is illuminated in a warm glow. Community theater. It is the earliest introduction I received to live theater. My mother was a volunteer for a theater in the Cleveland suburb where I grew up — she did everything from costumes to props to stage managing. I remember playing with other young friends whose mothers were volunteers, eating Happy Meals picked up in a hurry at McDonald's, getting doted on by the actors, and experiencing that magic when someone who had just patted me on the head minutes earlier appeared transformed on stage. I was very young when Mom quit volunteering, finally drained by the number of requests for her time, but somewhere in the back of my head I've always carried with me these jumbled memories of grown-ups laughing and joking, working with one another, yet all the same, playing. Although I acted in high school and college productions, I've never treaded the boards of a community theater. I've never seemed to have the time or energy to audition for a show, although I still love to watch performances. In the fall of 2002, I conceive of a way to combine my love of journalism with my enjoyment of theater. Why not find a community theater group and follow them through the process of an entire production? Sit in on auditions. Attend rehearsals. Strike the set. Write about what I see and experience. Linda Sopp, a veteran central Ohio community theater director and actress, agrees to be my guide. Sopp is a plump, motherly woman, 58 years young, who quickly warms up to my request to shadow her as she directs an upcoming production of Bus Stop at Curtain Players. On a chilly evening early in December, I join Sopp and her production crew for a brief meeting at the theater. She holds her session in the light booth, a cramped loft reached by climbing a steeply-angled ladder. Seated on mismatched chairs in a circle around a large space heater that resembles a radiator are Dan McCarty, producer; Jim Brosnahan, lighting designer; Amy Valigora, stage manager; and Sue Rasche, production assistant. Sopp hand-picked each of them to work with her. She beams at her brood for a moment, pushes up the sleeves of her sweatshirt and officially embarks on the activity that will soon consume all of her free time. At the meeting, the group discusses costumes (how to make them look aged, where to acquire them), lighting (something simple, not too bright), set (how to make the diner counter look different than it did in a show last season) and props (get them soon, and in hands of actors.) Sopp spars productively with McCarty, the two of them tossing ideas back and forth until a consensus is reached. Valigora, Sopp's 29-year-old daughter, chimes in from time to time. She is Sopp's stage manager every time she directs. On Dec. 28, the set is built, right on the stage. Normally, set building would take place after rehearsals have started, but the theater is hosting a playwright's festival for three weekends in January, and the set needs to be finished so it can serve as a backdrop. The stage is small: only 15 feet deep by 36 feet wide, with no curtain, and no backstage. Extra flats and bits of wood are stored underneath the stage and in a small shed next to the building. Props often are stored in homes, or borrowed. As Sopp tells me: ``When a Curtain Players person is in your house, they're taking inventory." With a production budget of $600 per show, borrowing and reusing isn't just a nicety, it's a necessity. Almost all of Sopp's production crew are present, joined by set designer Rich Tolliver and his wife Shelly, and a couple other CP members. I arrive at 10 a.m., and the flats are already in position and drills are buzzing away. The mood is upbeat, Elvis music blares from a boom box, and Sopp consults as problems are encountered. By 4:30 p.m., the bulk of the set is finished, and awaits painting the following Saturday. Auditions take place Jan. 12 and 13. ``This is the face of a happy director. We've got some really good people here," Sopp tells me a little before 7 p.m. as the theater fills with hopeful actors. A steady buzz of conversation, combined with a lot of hugs and bursts of laughter, makes the theater seem like the location of a good party. Most everybody seems to know one another. Over the course of this evening, and the next, Sopp will see a couple dozen actors audition for eight roles. Assisting her with casting are McCarty, Valigora, Brosnahan and CP member Sherry Erickson. They hold hushed meetings in the light booth several times, even meeting in the theater's single seat bathroom once to save the time and bother of climbing upstairs. Actors are judged not only on how they read at the audition, but on how they've worked in previous shows (he had trouble with lines, she grows into a role) and how they appear on stage next to one another (she looks a bit young, he's not tall enough.) At the end of the second night, Sopp — on the verge of tears — gives a heartfelt thanks to everyone who auditioned and reads out a list of her cast: Pollitt as Grace the diner owner; Radomski as Elma the waitress; Michael Stranges as Carl the bus driver; James Speegle as Dr. Lyman the professor; Michael Schacherbauer as Will the sheriff; William Koruna as Virgil the older cowboy; Miranda Lynn Hinton as Cherie the chanteuse; and Isaac Nippert as Bo the younger cowboy. Sopp holds a read-through two nights later at the Westerville Senior Center, where she is employed as an activities coordinator. She invites everyone to introduce themselves. I learn that Radomski is a high school student who aspires to be an actress, Koruna played the role of Virgil in a 1983 CP production, Nippert was a theater major at Ohio University and Speegle, Schacherbauer, Pollitt and Hinton have all done semi-professional or professional acting. Most of the cast has worked with one another on previous CP shows or at other theaters, but Nippert and Pollitt are brand new to the group. Personalities emerge: several members will be the comedians, others will be secondary directors, others will be quiet observers. Schacherbauer, a third grade teacher, is CP's artistic director, making CP one of only three community theaters in Ohio that have a paid staff member. Rehearsals begin in earnest on Jan. 19, with a Sunday afternoon blocking rehearsal at the theater. McCarty is there early on, to check with the actors about costumes, to determine what they might own already and what he'll need to find for them. ``This man is a thrift shop maniac," Sopp says with admiration. The show has three acts, and Sopp blocks each in a separate rehearsal. The actors stand on stage with scripts open in front of them like prayer books, pencils at the ready, and move where Sopp tells them to (cross upstage to table, sit on stool No. 4). Rehearsals normally start at 7 p.m. and run two to two-and-a-half hours, four nights a week. Ohio is having a harsh winter, and many nights, cast and crew shiver, wearing coats and drinking hot tea and chocolate to stay warm. The cast keeps Sopp, Valigora and me laughing regularly, even early on in rehearsals, with jokes both on and off-stage. Sopp can be very business-like at times, calling the group back to task with a no-nonsense voice, but she spends a good bit of rehearsals enjoying herself. She'll beam, planting her hands on her hips and rocking slightly back and forth, shaking her head as if to deny that she could truly be this happy. Her smile can be activated by an actor saying a line with just the right emphasis on a syllable, or by something as simple as admiring the appearance of two fake pies made by CP member Laura Havenec (using insulating foam, paint and Elmer's glue) that ``look soooo nice" on the diner's shelf. At tech rehearsal on Feb. 23, the light boards keep overheating. They will have to be rewired before tech week starts in earnest, on March 2. Sopp praises the cast for their patience as the run-through turns into a pause-through as various technical problems are dealt with, but she also admonishes them: ``My main concern is we've really got to get serious on lines and pick-ups," she says, during her post-rehearsal note-giving session, when the cast gathers in the theater seats and on the edge of the stage to receive Sopp's comments. ``Tonight was rough because we had people hanging from ceilings and beating snow machines, but we've got less than two weeks until we open." In spite of Sopp's fears, by tech week, lines are memorized and blocking is polished and up to performance level. In the week between, she held a line-through, a rehearsal dedicated to only running lines, starting back at the top of a script page every time someone forgets or paraphrases. For the final run-throughs, it is a treat to sit in the darkened theater, three or four of us scattered in the seats as the play unfolds before our eyes, a live movie. Nippert, as the headstrong cowboy Bo, struts his long legs across the stage and takes Hinton as Cherie, a buxom blonde in gingham and fishnets, into his arms. Speegle, who at auditions was a runner-up for the role of Bo, is eerily creepy as the middle-aged professor who alternately swills from his flask and smiles charmingly at the young Elma. Stranges as Carl, wearing his navy blue bus driver uniform, moves behind the diner's counter to nuzzle the red-headed Pollitt as Grace, after they spent time alone in her apartment, off-stage. In reality, in the tiny space allotted back stage, he's been reading a book and she's been knitting. By this point, the cast has gotten to know one another very well. A narrow room added on to the side of the theater with walls covered with the signatures of previous shows' casts serves as the dressing room for both sexes. ``We're theater people. It doesn't matter," Sopp said when she gave me my first tour of the theater. Backstage is Valigora's territory. She wears all black and a headset, and warns the actors of the impending curtain rising. ``15 minutes!" she'll call out, ``Pee, poop and props!" It is her job to be sure that every prop is in place, that all food served on stage is ready, that the snow machine is functioning. Her demeanor is calm and efficient, and serves as a counterpoint to the fidgety energy that most of the actors have prior to each performance. Nippert and Speegle always arrive early — Nippert to pace the theater and do vocal exercises; Speegle to hunker down on a stool at the diner's counter, running lines quietly. Opening night on March 7 sells out, and Sopp radiates pleasure, even as she deals with the duties she's assumed as house manager. (Not a director's usual responsibility, but one of many tasks she takes on at CP, including editing the newsletter, sitting on the board as business manager and organizing the theater's archives). I watch the play with her, upstairs in the lighting loft, on a comfortable couch positioned on an open edge of the loft. She watches the performance like a sporting event, making a fist and punching out her hand at the funny bits, leaning forward, leaning back, half-rising to her feet, settling back in, then shifting forward all over again. .     The show will go on seven more times — five more evening performances and two matinees. Although every performance doesn't sell out, a respectable number of people fill the house each time. By the end of its run, a Sunday matinee on March 23, the weather is a balmy 60 degrees and sunlight streams in through the open doors at 4 p.m. as the audience filters out after the performance. The cast and crew have to stick around, though, for a couple more hours, to take apart the set they've occupied for the last two months. Piece by piece the flats that made up the walls of Grace's Diner are dismantled; the pot belly stove, the refrigerator and the cash register are lugged outside to a truck to return to another community theater; screws are collected; and the floor is swept. ``Halleluiah. There we are," Sopp says quietly at 5:40 p.m. when the last flat touches the ground. She herds the cast and crew into the seats and begins the presentation of Ham Mugs, a CP tradition after every show. Sopp makes a small speech about each person present, and gives each one a mug personalized with stickers representing their character. ``I heard over and over again, that the casting was great. You guys just took this show and ran with it. Great show! Thank you so much!" she says, and receives applause in return. As Sopp's cast and crew exchange hugs and farewells, the cast and crew of Play On, the next show in CP's season, begin to arrive. Set building is scheduled to begin at 6 p.m., and as Valigora and Sopp load the last few items from Bus Stop into the back of their cars, the Play On group stands in the doorway.

The next show must go on. ©2003 Susan K. Wittstock

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Got Something To Say? Make your point and get published with a Letter To The Editor. We'd like to hear from you no matter how pointed you are. For some good reading give a Click! to the editor |

© 2003 Aviar-DKA Ltd. All rights reserved (including authors' and individual copyrights as indicated). No |

The road curves slightly to the left, then right, and I brake when it dead ends into another. In front of me, a small white sign that once advertised real estate now features a red arrow pointing right, underneath simple black lettering: Curtain Players. A quarter-mile down the road, a bright street light shines from its post in a

gravel parking lot. I have arrived at the home of Westerville, Ohio's community theater group, a wood and brick church dating back to 1836 that now welcomes audiences instead of congregants, actors instead of preachers. Outside, its sturdy white steeple still points skyward, though inside, its pews and pulpit have long since been replaced with theater seats and a stage.

The road curves slightly to the left, then right, and I brake when it dead ends into another. In front of me, a small white sign that once advertised real estate now features a red arrow pointing right, underneath simple black lettering: Curtain Players. A quarter-mile down the road, a bright street light shines from its post in a

gravel parking lot. I have arrived at the home of Westerville, Ohio's community theater group, a wood and brick church dating back to 1836 that now welcomes audiences instead of congregants, actors instead of preachers. Outside, its sturdy white steeple still points skyward, though inside, its pews and pulpit have long since been replaced with theater seats and a stage.  This year, Curtain Players is putting on six shows and is celebrating its 40th anniversary season. By our second meeting, Sopp briskly offers to consider me a member of her production staff, providing me with access to her and her crew as they put this production together. We meet a couple of times in November at a coffee shop, and

she outlines for me her background in and devotion to theater. ``I tell people the only reason I work is so I can do this at night," she says.

This year, Curtain Players is putting on six shows and is celebrating its 40th anniversary season. By our second meeting, Sopp briskly offers to consider me a member of her production staff, providing me with access to her and her crew as they put this production together. We meet a couple of times in November at a coffee shop, and

she outlines for me her background in and devotion to theater. ``I tell people the only reason I work is so I can do this at night," she says.