|

It was a wintry day in 1964 when I slipped into the family circle standing room section of the old Metropolitan Opera on 39th Street and Broadway in Manhattan. I had convinced my overprotective mother to allow me to go – unchaperoned! – to New York to hear La Boh├Ęme. I had been listening to it on my grandfather’s old 78s and vinyl recordings for years, along with all the other staples of the Italian repertoire, but I wanted to SEE a performance onstage. It was the theatre, as well as the music which gripped me, and in that last year of the glorious old house, I wanted to experience the magic. From the moment the curtain went up on the Paris garret to the heart rending cries of “Mimi!,” I was transported to another place, a realm that captivated me and has continued to hold me in thrall for over fifty years.

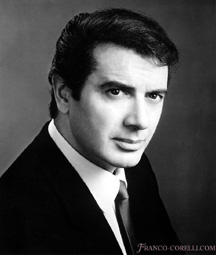

The Mimi that evening was the luminous Renata Tebaldi, past her prime and a little mature for the young seamstress, but who could still spin a velvety tone so laden with emotion that it was impossible to resist. And the tenor was Franco Corelli. He was the first of several singers who would play significant roles in shaping my artistic psyche. There have been four tenors in my life– voices which struck to the soul at different crossroads in my experience, voices which filled my imagination, opened new worlds, and inspired me in my own work.

My addiction to the tenor voice began with Franco Corelli, whose sheer visceral power introduced me to the world of opera with its great passions and sweeping pageantry. I was a high school senior, who had planned to commit myself to the arts, theatre, and literature. The second was the riveting Peter Hofmann, to whom, with his enthusiasm for Wagner my late husband introduced me. I met Peter at a point in my life when I was changing careers, finding a new voice for myself as a journalist, and it was the world of German opera which he embodied that led to my first book on Heldentenors and a subsequent career as a music journalist. The third was Jerry Hadley, whose ineffably sweet lyric voice had an incomparable purity. Because I worked with Jerry on so many projects in my capacity as assistant to Thomas Hampson, he was a friend as well as an inspiration, and his tragic death has done nothing to dim my memories of the joy his voice and he, himself, brought to others around him. (Hampson is the baritone of my title, another artist whose work has inspired me and with whom I enjoyed a decade long collaboration that took me all over the world of classical music- but because I was working “in the trenches” in the industry, those experiences have the flavor of reality rather than idealized beauty, and they constitute quite another story!) The last and latest of these tenors, Jonas Kaufmann, has a voice that awakened me from a dark period in my life and helped me find my way back to opera and classical music which have always been so much a part of my existence. As I reflect on my years of involvement with opera, I try to evaluate not only the voices I have loved as I now hear them, but also to appreciate the shaping impact they have made on my artistic consciousness.

Franco Corelli was a force of nature, a singer with a huge, virtually self-taught voice that pulsated with Mediterranean passion and fire. There was nothing restrained or “tasteful” about his singing; it was full throttle emotion and glorious sound from start to finish, but as such it swept the audience away with the majesty of the music and the monumental power of the drama. His ringing top remains a sound so unique and thrilling as to send shivers from recordings even today. He had an expansiveness of line, a generousness of tone, an abandon of feeling in everything he sang. In the Italian repertoire he was supreme; he understood these virile, larger-than-life heroes because in some ways he, too, was a character larger-than-life in an age when it was expected for a star of his magnitude to be a divo. Who can forget his tearingoffstage, rapier in hand to challenge Boris Christoff or his “anything you can sing I can sing louder” wars with Birgit Nilsson in Turandot or his repeated shouting matches with his feisty wife Loretta at the stage entrance?

But Corelli, for all his flamboyance, was serious about his art, and he worked hard to shore up his technique, refine his musicality, and expand his repertoire. If his French roles like Werther, Romeo, or Don Jos├ę always sounded as if he were singing in an indeterminate tongue, he nonetheless, put his own stamp of excitement and luxurious sound into the characterizations. And no small part of that excitement came from the dashing figure Franco Corelli cut on stage. Tall, athletic, handsome with chiseled Roman features and curly dark hair, he made a believable romantic lead. And more so than so many of his contemporaries, he worked at building a character; true, he was not above acknowledging the often tumultuous applause that interrupted opera in those days, but he was able to sustain a level of dramatic verity that distinguished him among his peers.

Through Franco Corelli, whose every New York performance I followed throughout my college days and into the first years of my marriage until he retired prematurely in 1976, I not only began my fascination with opera, but also with glorious the mysteries of the human voice – and the tenor voice, in particular. I became acquainted with the breadth of the belcanto, verismo, and romantic Italian and French repertoire, I began my huge collection of recordings and scores. And while our young married life amidst the chaos of Vietnam, teaching, and social activism often took me to places remote from the fantasy realms of opera, Franco’s voice remained for me a sound of solace, of beauty, of possibility.

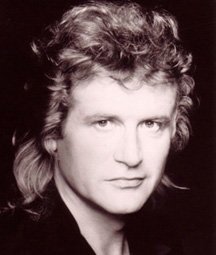

When I encountered Peter Hofmann, my husband Greg and I were at a crossroads in our lives, having moved back from the Midwest to New York and in the process of changing careers. Greg, while he shared my love for Italian and French opera – he would unfailingly burst into tears at the first strains of Un bel d├Č – adored Wagner, and it was he who introduced me to German opera, a passion we both pursued when we returned to New York in the 80s. There in 1986, we found ourselves at the Met at a performance of Lohengrin. The Swan Knight was Peter Hofmann, and I remember experiencing something that might have been akin to what Mad King Ludwig felt when he responded to the mysterious hero. Though I was familiar with the opera and had seen it several times in the 60s, I had previously found the singing prosaic and the staging rather unimaginative. I needed a singer to reveal to me the inherent beauty, the complexity, romanticism, and expressiveness of Wagner’s writing. Suddenly, there on the stage of the Metropolitan, bathed in a shimmering silvery light, blond, tall, impossibly handsome, stood the Lohengrin of one’s dreams, and when he opened his mouth the sing, “Nun sei bedankt, mein lieber Schwan” I heard the exquisite music sung with a poetry, passionate conviction, and subtle, mysterious character motivation. I was completely and irrevocably swept away!

And so began for me a voracious search for an understanding of this mesmerizing artist and his milieu of the Heldentenor repertoire. It was a quest that led me to research every review, every interview, book, listen to every video, recording, and private tape available, and to see every performance Peter did in New York, as well as traveling to Bayreuth and Hamburg. In the process, my enthusiasm spilled over into all things German. I learned the language so well I was able to translate Hofmann’s first book, Singen ist wie Fliegen, and go on to commit myself to a two-year project writing my own study of Heldentenors,We Need a Hero! (Weiala Press 1988), which, in itself, opened doors for me as a music journalist, so that by 1990 I was working full time as a critic covering the New York and international opera and classical music scenes.

When I first met Peter Hofmann, he was in his prime, at the height of his fame as an heroic tenor and topping the pop charts with his rock and crossover ventures. Within a short time he would face withering criticism for his pop forays and his alleged “abused operatic voice,” and sadder still, his career would ultimately be felled by Parkinson’s disease which caused him to retire in 2000 and pass away at sixty-six a decade later. None of these twists of cruel fate, however, has ever diminished the bright place his artistry holds in my memory.

At its best, Hofmann’s voice was large (but not huge in the Melchior mold) with a pleasing blend of baritonal heft and ringing metallic radiance. He was an intelligent musician, more sensitive to legato and dynamics than many heroic singers of his day. But most of all, he was a singing-actor, a stage animal who brought to life each of his roles with a cinematic intensity, a touch of revolutionary zeal, and a broad swath of abandoned romanticism. When he took the stage, a century of stuffy Wagnerian drama seemed to go up in smoke; there was a modernity and credibility to his Siegmund, Tristan, Parsifal, and Lohengrin. Moreover, there was a kind of protean energy – the ability to transform completely into character, as well as the ability to constantly push the polite rules of classical music and break the barriers among media and genres. Perhaps what stays with me most now that Peter is gone (and I have the honor of working with his brother and manager Fritz on his memorial website), is his daring and his courage – certainly as a human being faced with an impossible affliction, but also as an artist who valued passion above perfection. Many of Peter Hofmann’s friends have remembered him as “larger-than-life” and yet very approachable – (something I, too, found in our meetings) -and it was this combination of the intensely human and the entrancingly heroic that set him apart.

By the mid 1990s I had temporarily abandoned my reviewer’s tasks to become baritone Thomas Hampson’s assistant, a decade-long collaboration that allowed me to participate in and co-author a great many exciting artistic projects, musical research, and share so many musical, theatrical, and media experiences first hand. In those years, tenor Jerry Hadley was not only the reigning American lyric tenor of the day, but he was one of Hampson’s closest friends and a frequent concert and opera collaborator. As such, I naturally got to know Jerry very well and to hear him in so many memorable performances. (I’ve reminisced about these in my earlier tribute:

A Sweetness in Every Woe - Scene 4 March 2014).

But actually my first acquaintance with the voice goes back to the 1980s at the New York City Opera, where among the numerous unforgettable roles he created there, was a searing Werther. At the Met he was an incomparable Almaviva, Des Grieux, Lensky, and Nemorino. A prolific recording artist, recitalist, and champion of so called “crossover” music, Jerry shone in roles like Candide or Gaylord Ravenal, at the same time that he could tear your heart out with his renditions of Viennese operetta or Broadway show tunes.

|

Of my four tenors, Jerry Hadley was the most lyrical, and he wisely remained within his natural range throughout his career, finding breadth and diversity in the styles of music he interpreted. The voice had an ineffable sweetness, a liquid luminosity, a melting use of the head register, and an arresting way with words. Text in any language he sang came across with a clarity and naturalness that struck to the heart, and his characterizations were unabashedly emotional and sincere. Moreover, he radiated an animation, a kind of finely wired energy, not only on stage, but in a room of people. Jerry’s very presence insisted that you pay attention to him, to what he was saying (or singing), that you like him as much as he liked you. He was able to create with his acquaintances and friends, of course, but also with his public, that intangible bond of sympathy and attachment. His tragic death in 2007 left all of us who knew and loved him as a person and an artist utterly bereft.

When I left my employ with Thomas Hampson, I took a break for a while from opera and journalism. I was burned out after a decade of frequent travel, devastated by 9/11, and felt the need to concentrate on my husband and my plans for “retirement.” While we did realize that chimera of happily-ever-after in a newly built house on the coast of Maine for ten short months, the idyll was cut short by Greg’s sudden heart attack in February 2010. The process of grieving and rebuilding a new life – one which now includes a return to journalism and the arts – has been arduous, and it was during these dark days that another voice began to speak to me.

It was a Saturday afternoon in March that I first saw and heard Jonas Kaufmann as Werther at the Met. My step was lighter as I left the theatre, and I felt as if a dark curtain had been lifted allowing light to pour into my soul once again. The voice, the actor, the presence spoke to me once more about the transformative power of beauty and poetry in the human voice.

And what a voice – an instrument unique in its timbre, its range, its versatility! A voice which, by his own admission, was not always the miracle it is today – a voice which had to be discovered, liberated from somewhere deep within the artist and nurtured and developed in its singularity. It is a dark, distinctive, powerful voice, which despite the exceptional colors of each register, has an evenness and ease throughout the range. The chest register is baritonal in the Heldentenor sense; the middle is veiled, dusky, erotic, and the top then explodes in a thrilling open ring.

Moreover, it is a voice which is governed by a masterful technique. His pitch is firm; his attacks are clean; he moves comfortably among the registers, often carrying the middle higher into the head voice than many a tenor. Kaufmann demonstrates one of the most expressive and far-reaching dynamic ranges of any tenor in memory, and he uses these colors and shadings with refined musicianship. His phrasing is a breathtaking combination of confident legato, elegant portamento, and just enough rubato to satisfy the dramatic demands of the music. His line has an Italianità which allows him to approach every role from a bel canto foundation.

Yet, that said, he is the master of idiomatic style in whatever language he sings. Accomplished as a speaker and singer in his native German, as well as Italian, French, and English, he brings to every characterization that intimate identification with the text that marks a great artist.

The synthesis of these vocal qualities is joined to an incredibly riveting stage presence. Jonas Kaufmann is une b├¬te de sc├Ęne, par excellence. As only a few other great tenors before him, Kaufmann is an actor whose physicality, sensitivity, vulnerability, and essential humanity give him a cinematic intensity on the stage. Not only does he cut a striking, romantic figure, and move with a compelling athleticism, but he is attentive to the smallest gesture that grows out of the music and the inner reality of the character. His building of a role is almost Method-acting in its intensity and in the level of truth which he seeks. But what amazes the most, perhaps, is the indescribable sensation one has when watching and listening to him that the words and emotions he is conveying are REAL, that they come from somewhere deep within and are communicated in the white-hot truth of the moment. Jonas Kaufmann is an artist who experiences the emotions he shares, and it is this unsparing willingness to plumb the depths of a character that make his stage incarnations unforgettable.

Finally, there is the anomaly of the career which Jonas Kaufmann has chosen to construct that assures him a special place among today’s singers and in the history of opera. There are precious few singers whose repertory has the breadth of Kaufmann’s. Today, only the amazing Placido Domingo, thirty years Kaufmann’s senior, can boast such a diverse list of roles. Challenging the conventional wisdom of today’s classical music models, taking the risk to insist on singing Faust at the same time as Siegmund, Kaufmann has revived the golden age of singers of the past, daring to take their versatility as far as he can, stretching his own gifts and reaching for new challenges.

And what is so thrilling about all of this is that Jonas Kaufmann, as I write, is not yet forty-five years old. He is in his prime, and with his intelligence and his passion for his art – and with the good graces of the Fates – has so many more memorable creations to shape. [1]

As I revel in this thought, I pause to ask myself why I have always been so fascinated with the tenor voice in particular? And why this short list of artists who have occupied such a special place in my artistic sensibility? There is something unarguably erotic in the tenor sound, as well as something mysteriously inspiring. By definition, the range is higher than what is considered a natural one for a man, and perhaps it is that sense of “pushing the limits”, seeking a rare height, and transcending the reach of “mere mortals.” There is something wonderfully impossible, even miraculous in the sound of a beautiful tenor.

Then, too, my discovery and association with each of these artists (personally, and/or professionally) has coincided with moments of change or decision in my life. It has been as if their artistry became the inspiration to lead me forward, open new doors of inquiry and fill my being with a sense of wonder and magic. From my youthful passion for Franco Corelli to my current admiration of Jonas Kaufmann, more than forty years have passed, but they have been years filled with music, with opera, with theatre both in a recreational and professional sense. As I made my way from teaching to the classical music industry and finally to freelance arts journalism and criticism, I have been accompanied by these Muses. As a critic I have sometimes come to “hear” - and have had to acknowledge - flaws in these tenor heroes, but even the admission that an attack is blurred or a pitch is shaky, has done nothing to diminish the impact these four singers have made on my soul.

For me, Franco Corelli, Peter Hofmann, Jerry Hadley, and Jonas Kaufmann, - despite their different styles and repertoires - share a special aura. As artists, they each appear to embody the mythic truths of love, human suffering, and transcendent poetry in their music. And most of all, they are blessed with the gift of making the ideal seem real.

1. These passages are excerpted from my forthcoming book,

Jonas Kaufmann Passion and Poetry. A Critic’s Diary. Weiala Press. C.2017

|