|

It was the author’s first book. She had lived with a writer for almost 40 years, but was not a writer and once said, “everything has been written about” when asked to write about her life. But, ultimately she did write a book and now, 60 years later, The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook, is one of those rare books which has never been out of print since its November, 1954 debut.

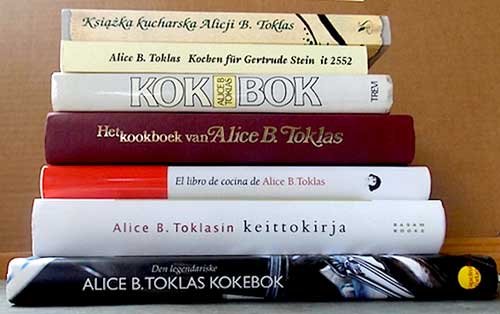

The cookbook has been translated into more than 15 languages. The most recent foreign edition is the Norwegian paperback, whose publisher, Grapefrukt Vorlag, commissioned ten contemporary artists to create a portfolio of new cookbook illustrations in celebration of the 60th anniversary. (Alice’s cookbook was published seven years before Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Julia and Alice met at Hemingway’s son’s wedding in Paris in 1949.)

Should anyone be surprised at the long-term success of Alice’s cookbook?

No, since Alice B. Toklas lived no ordinary life, was no ordinary cook and her bestseller is no ordinary cookbook. Yes, it has recipes, but it is also a book of stories interspersed with recipes - stories of her fascinating life with Gertrude Stein. There are tales about problems with servants, survival during wartime, meals for and with friends, and travels, many in their beloved cars - Gertrude at the wheel, Alice navigating and their white poodle, Basket I or II, holding on tight!

Friends are an important part of the cookbook. A friend, British painter, Sir. Francis Rose illustrated both the first American and British editions. A bold drawing of Alice highlights the dust jacket of the British edition. Longtime friend, Picasso, has a special fish dish prepared for him. A friend’s recipe for hashish fudge is undoubtedly one of the reasons the book became famous and remains famous. The editor of a now defunct food magazine reprimanded me when I implied in a letter to the editor that the “brownie” recipe might have been the cookbook’s primary claim to fame. Her reply:

“ …I think you do Ms. Toklas a disservice when you say she's remembered largely for that brownie recipe. In food circles she is widely revered not only for her recipes, which are wonderful, but also for her unique recipe writing style.”

The foodie editor not withstanding, it was artist Brion Gysin’s recipe for “Haschish Fudge,” on page 259 of the 1954 British first edition, which made Alice B. Toklas and her cookbook famous and infamous. The recipe, in addition to the cannabis, is a blend of spices, dates, figs, nuts, sugar and butter. It did not appear in an American edition until the 1960 paperback was published, just in time for the Beats and a few years later for the Age of Aquarius generation who morphed the concoction into its brownie version. The recipe appears in the cookbook’s dessert section. I’m sure that Peter Seller’s 1968 film, “I Love You, Alice B. Toklas,” caused the sales of Betty Crocker brownie mixes to reach new heights!

Gysin’s recipe is included in the chapter “Recipes from Friends,” which came about because Alice realized her manuscript was several pages shorter than the publisher had requested. She frantically wrote letters to her BFF list. Among others, she received recipes from Virgil Thomson, who sent recipes for shad-roe mousse, gnocchi a la Piedmontese and pork a la pizzaiola of Calabria; Cecil Beaton, whose iced apples dessert is described as “a Greek pudding, very Oriental;” Carl Van Vechten and his wife Fania Marinoff sent five recipes; and Natalie Barney, probably not a BFF, whose simple recipe for stuffed eggplant with sugar begins a section on vegetables. All in all the friends’ recipes filled thirty-five pages which satisfied her editor. That’s what friends are for!

|

Getting Alice’s cookbook (or “cook book,” as it was spelled in earlier editions,) written was a lifelong journey. Cooking and supervising cooks had been a part of Alice’s life in her upper-middle class home in San Francisco from the time she was a young woman. Her mother died when Alice was nineteen, and by then she had assumed total responsibility for taking care of a household of men – her father, her young brother, Clarence, and her grandfather. Alice collected household recipes during those years and tucked them away in her luggage when, at the age of thirty, she decided to begin her independent life in Paris in 1907.

On the first day she arrived in Paris, Alice met Gertrude, the sister of Michael Stein whom she had known in San Francisco. It was infatuation at first sight, which ushered her into a new domestic situation, one that she appeared to have chosen gladly. She moved in at 27 rue de Fleurus three years later, after Leo Stein moved out unceremoniously as the result of a number of spats with sister Gertrude, over various artists of the day and good, old-fashioned sibling rivalries over who was the best writer or had the best taste.

The recipes that Alice had collected were now ready to be used even though she only cooked on Sunday evening. It is not until the beginning of chapter 3, following chapters on “The French Tradition” and “Food in French Homes,” that she proudly introduces her connections with “simple” American food in the chapter “Dishes for Artists.”

“Before I came to Paris I was interested in food but not in doing any cooking. When in 1908 [sic] I went to live with Gertrude Stein at the rue de Fleurus we would have American food for Sunday-evening supper, she had had enough French and Italian cooking; the servant would be out and I would have the kitchen to myself. So I commenced to cook the dishes I had eaten in the homes of the San Joaquin Valley in California – fricasseed chicken, corn bread, apple and lemon pie. Then when the pie crust received Gertrude Stein’s critical approval I made mince-meat and at Thanksgiving we had turkey that Hélène the cook roasted but for which I prepared the dressing.”

In addition to the bass prepared for Picasso, which Alice decorated with tomato-paste-colored mayonnaise, this chapter includes a recipe given to Alice by the artist Francis Picabia for very, very slow scrambled eggs. Though the recipe is simple, just eggs, salt and pepper, the fourth ingredient, ½ a pound of butter (that’s two sticks!), are Alice’s recipes for the contemporary, olive oil-centric, Food Network addicted cook?

From the standpoint of ease of preparation, many of the recipes are easy and don’t require exotic or unattainable ingredients. Some ingredients are probably more accessible today than they were in the 1950s and 1960s. But recipes do call for large amounts of butter, lard, heavy cream and eggs. Her “Potatoes Smothered in Butter,”(no kidding!) uses 1½ sticks of butter for two pounds of potatoes. A friend of mine says they are the best and also swears by Alice’s “Liberation Fruitcake,” which he makes every Christmas. The first one was delivered to an American general whose troops liberated the Vichy region of France where Stein and Toklas were living during World War II. There are twelve eggs and a pound of butter in the fruitcake, but it makes twelve pounds of fruitcake to gift and re-gift.

For other cooks, the layout of the recipes may initially be disorienting. Some are incorporated into anecdotes, while the ingredients for all of them are written into paragraphs that describe the cooking steps. Once one has read a few of them and the charming stories that frame them, it is no longer an issue.

Of the book’s thirteen chapters, one of them, “Murder in the Kitchen,” has become iconic because of Alice’s tongue in cheek parallels between homicide and a cook’s tasks:

“When we first began reading Dashiell Hammett, Gertrude Stein remarked that it was his modern note to have disposed of his victims before the story commenced. Goodness knows how many were required to follow as the result of the first crime. And so it is in the kitchen. Murder and sudden death seem as unnatural there as they should be anywhere else…The first victim was a lively carp…I carefully, deliberately found the base of its vertebral column and plunged the knife in…Horror of horrors, The carp was dead, killed, assassinated, murdered in the first, second and third degree. Limp, I fell into a chair, with my hands still unwashed reached for a cigarette, lighted it and waited for the police to come and take me into custody.”

The popularity of this chapter has resulted in the publication of a paperback as part of the Penguin Great Food series. (The hashish fudge recipe is also included, a clever marketing move.)

Three chapters are favorites: “Food in the United States 1934 and 1935,” “Food in the Bugey During the Occupation,” and “The Vegetable Gardens in Bilignin.”

Stories and recipes in the food in the U.S. chapter chronicle Stein’s seven-month lecture tour following the phenomenal success of her first best seller, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. The chapter begins with Stein’s concern that food in her native land will be inedible based on stories she’s heard including a report that many Americans cook with food out of tin cans. Once she is assured that is not the case, the lecture and food tour across the continent commences. There is lots of name-dropping, but Alice and Gertrude had an address book full of names that could and should be dropped. There are meals with Thornton Wilder, Sherwood Anderson, the Harcourts of publishing renown, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. A clear turtle soup in Chicago was “memorable” according to Alice, while in Lansing, Michigan they had bird’s nest pudding, “a dessert we should not neglect,” and in San Francisco “we indulged in gastronomic orgies.”

The other two chapters are closely linked. Their vegetable gardens were instrumental in their survival during the Nazi occupation of France. The tales of depravation, “with economy the ten pounds [of real China tea] friends had sent us in the summer of 1939 lasted us till the Liberation,” are interspersed with harrowing accounts of wartime life, “suddenly we had Germans billeted upon us, two officers and their orderlies…How the Germans cooked, has no place in a cookbook…” There is, however, Alice’s signature humor, which comes through and is telling at many levels, “In the beginning, like camels, we lived on our past.” Photographs from the latter years of the war show the physical toll it had taken on both of them.

The cookbook ends with Stein and Toklas leaving their country garden for the last time about six months before the Liberation. The sadness of the moment is punctuated with optimism and Alice takes one more stab at her writing ability:

“Our final, definite leaving of the gardens came one cold winter day, all too appropriate to our feelings and the state of the world. A sudden moment of sunshine peopled the gardens with all the friends and others who had passed through them. Ah, there would be another garden, the same friends, and possibly, or no, probably new ones, and there would be other stories to tell and to hear. And so we left Bilignin, never to return.

And now it amuses me to remember that the only confidence I ever gave was given twice, in the upper garden, to two friends. The first one gaily responded, “How very amusing.” The other asked with no little alarm, “But Alice, have you ever tried to write? As if a cookbook had anything to do with writing.”

It does. Happy 60th Anniversary!

|